Round the world flight - LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin Airship Story

- Synopsis -

LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin (Deutsches Luftschiff Zeppelin 127) was a German passenger-carrying, hydrogen-filled rigid airship that flew from 1928 to 1937. It offered the first commercial transatlantic passenger flight service. Named after the German airship pioneer Ferdinand von Zeppelin, a count (Graf) in the German nobility, it was conceived and operated by Dr. Hugo Eckener, the chairman of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin.

The Graf Zeppelin was the designated registration of D-LZ127 (Deutsche Luftschiff Zeppelin number 127) the 127th designed Zeppelin, was originally planned to exploit the latest technology in airships, building on the advances of the earlier commercial operational ships. After the First World War, Germany was limited by the treaty of Versailles to the size and capacity of ships which they could build. The Zeppelin Company had created two ships within this limited size parameter, the Bodensee and Nordstern, for small inter city passenger services. It was with a contract with the United States Government that enabled the company to exceed the regulation laid down on the size limitation, and thus designated and constructed the D-LZ126, later re-christened on delivery as the "Los Angeles". Much of the lessons learnt in the design of this ship, was carried forward and improved in to the design of the LZ-127 "Graf Zeppelin".

Dr. Hugo Eckener, whose experience and work with Count Zeppelin had lead the company for the years following the death of the Count, had to campaign to the German Government for its construction and assisting funding, and only after two years of lobbying did that proceed at the Zeppelin works, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, at Friedrichshafen in Germany.

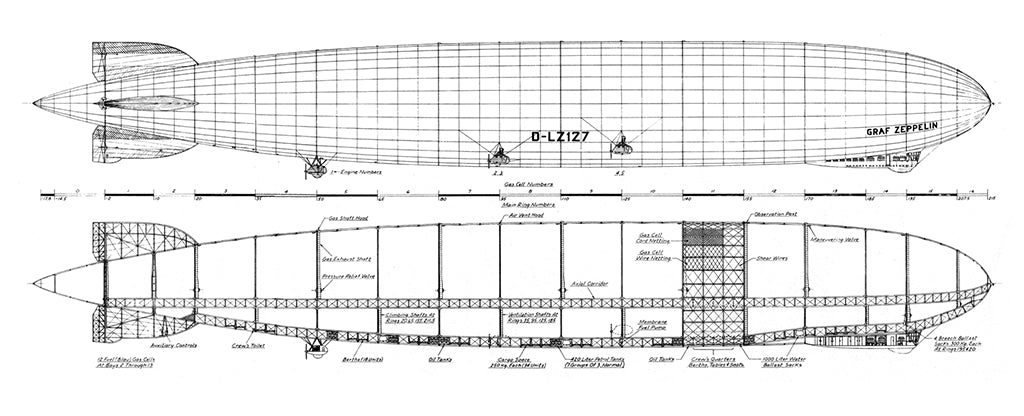

Construction of the ship began on the enhanced design of the LZ126, and when finally complete, the ship flew for the first time on 18 September 1928. With a total length of 236.6 metres (776 ft) and volume of 105,000 cubic metres (3,700,000 cu ft), was the largest airship up to that time.

The D-LZ127 was powered by five Maybach 550 horsepower (410 kW) engines that could burn either Blau gas or gasoline. The ship achieved a maximum speed of 128 kilometres per hour (80 mph, 70 knots) operating at total maximum thrust of 2,650 horsepower which reduced to the normal cruising speed of 117 km/h (73 mph).

The D-LZ127 had a usable payload capacity of 15,000 kilograms for a 10,000 kilometres cruise.

Initially it was to be used for experimental and demonstration purposes to prepare the way for regular airship travelling, but also carried passengers and mail to cover the costs.

Graf Zeppelin made 590 flights totalling almost 1.7 million kilometres (over 1 million miles). It was operated by a crew of 36, and could carry 24 passengers. It was the longest and largest airship in the world when it was built. It made the first circumnavigation of the world by airship, and the first nonstop crossing of the Pacific Ocean by air; its range was enhanced by its use of Blau gas as a fuel. It was built using funds raised by public subscription and from the German government, and its operating costs were offset by the sale of special postage stamps to collectors, the support of the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, and cargo and passenger receipts.

After several long flights between 1928 and 1932, including one to the Arctic, Graf Zeppelin provided a commercial passenger and mail service between Germany and Brazil for five years. When the Nazi Party came to power, they used it as a propaganda tool. It was withdrawn from service after the Hindenburg disaster in 1937. It was dismantled in 1940 on the orders of Luftwaffe Marshal Hermann Göring at the time, and the aluminum that made up its hull skeleton was diverted for armament production.

During its career, the D-LZ127 Graf Zeppelin flew more than one and half million kilometres over 590 flights, and made 144 ocean crossings, carrying 13,110 passengers.

With a perfect passenger safety record, making it the most successful rigid airship ever built.

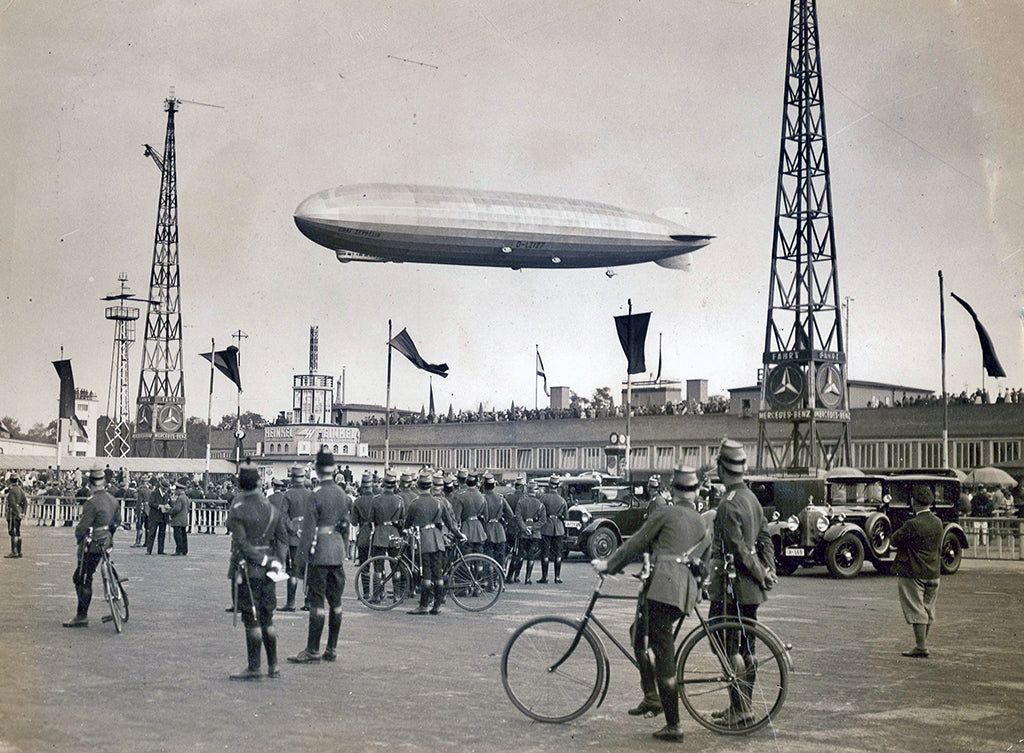

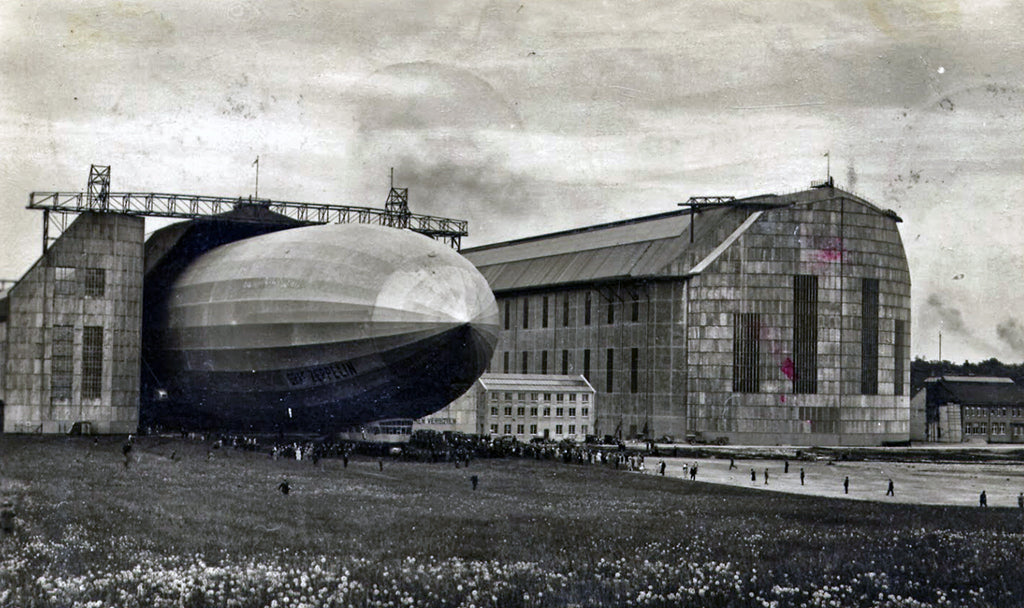

Graf Zeppelin at its Friedrichshafen Hangar

Graf Zeppelin at its Friedrichshafen Hangar

- Design and Technology -

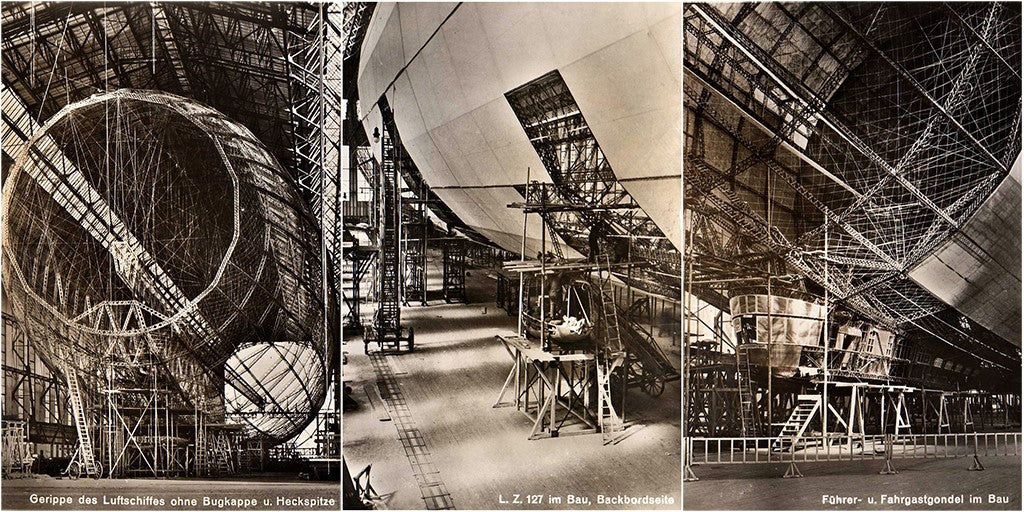

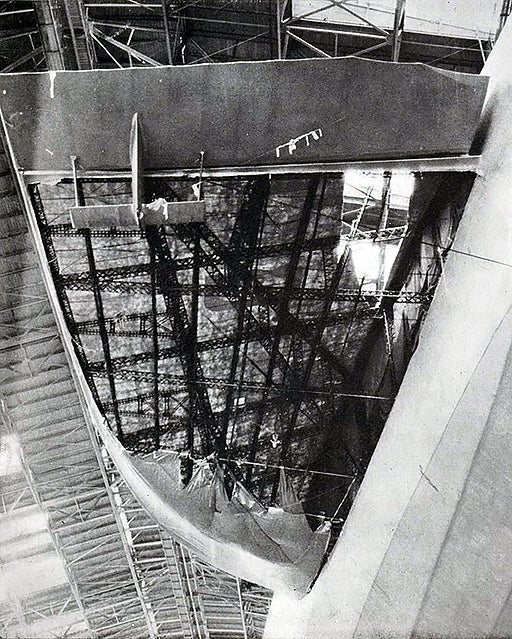

The LZ 127 was designed by Ludwig Dürr as a "stretched" version of the zeppelin LZ 126 rechristened the USS Los Angeles). It was intended from the beginning as a technology demonstrator for the more capable airships that would follow. It was built between 1926 and September 1928 at the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin works in Friedrichshafen, on Lake Constance, Germany, which became its home port for nearly all of its flights. Its duralumin frame was made of eighteen 28-sided structural polygons joined lengthwise with 16 km (10 mi) of girders and braced with steel wire. The outer cover was of thick cotton, painted with aircraft dope containing aluminium to reduce solar heating, then sandpapered smooth. The gas cells were also cotton, lined with goldbeater's skins, and protected from damage by a layer containing 27 km (17 mi) of ramie fibre.

Graf Zeppelin under construction

Graf Zeppelin under construction

Graf Zeppelin was 236.6 m (776 ft) long and had a total gas volume of 105,000 m3 (3,700,000 cu ft), of which 75,000 m3 (2,600,000 cu ft) was hydrogen carried in 17 lifting gas cells (Traggaszelle), and 30,000 m3 (1,100,000 cu ft) was Blau gas in 12 fuel gas cells (Kraftgaszelle). The Graf Zeppelin was built to be the largest possible airship that could fit into the company's construction hangar, with only 46 cm (18 in) between the top of the finished vessel and the hangar roof. It was the longest and most voluminous airship when built, but it was too slender for optimum aerodynamic efficiency, and there were worries that the shape would compromise its strength.

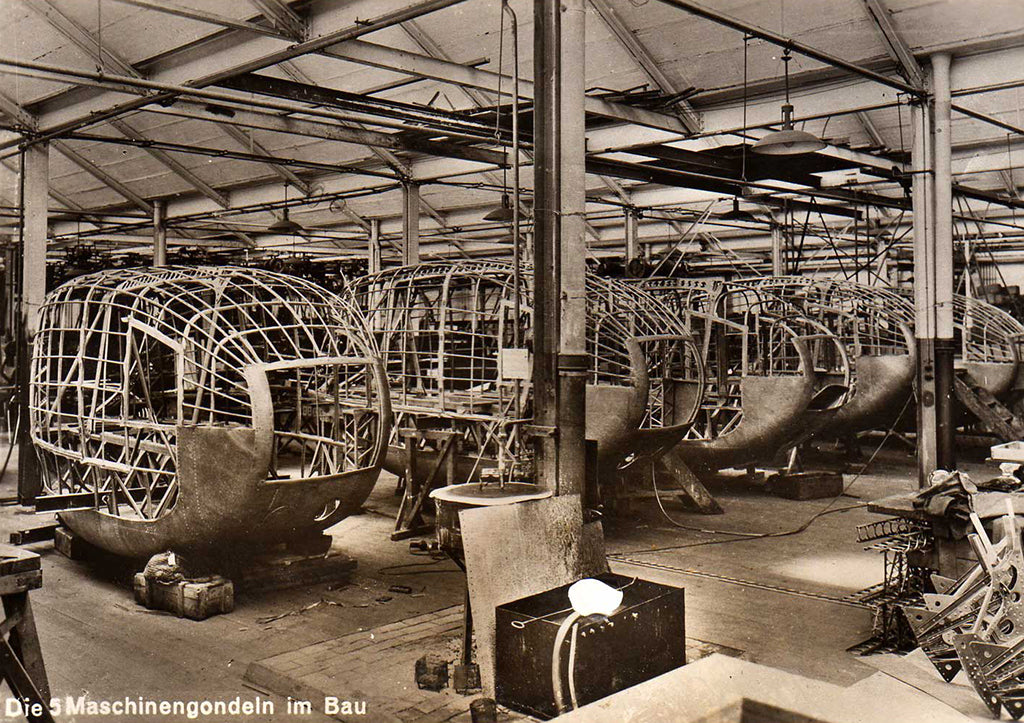

Graf Zeppelin’s five engine gondolas under construction

Graf Zeppelin’s five engine gondolas under construction

Graf Zeppelin was powered by five Maybach VL-2 12-cylinder engines, which could develop 550hp at maximum revolutions, and 450 hp at 1400 RPM in cruise, The engines are housed in separate, streamlined nacelles, each in undisturbed airflow. The engines were reversible, and were monitored by crew members who accessed them during flight via open ladders. The two-bladed wooden pusher propellers were 3.4 m (11 ft) in diameter, and were later upgraded to four-bladed units. On longer flights, the Graf Zeppelin often flew with one engine shut down to conserve fuel.

Graf Zeppelin was the only rigid airship to burn Blau gas; the engines were started on petrol and could then switch fuel. A liquid-fuelled airship loses weight as it burns fuel, requiring the release of lifting gas, or the capture of water from exhaust gas or rainfall, to avoid the vessel climbing. Blau gas was only slightly heavier than air, so burning it had little effect on buoyancy. On a typical transatlantic journey, the Graf Zeppelin used Blau gas 90% of the time, only burning petrol if the ship was too heavy, and used ten times less hydrogen per day than the smaller zeppelin L 59 did on its Khartoum flight in 1917.

Graf Zeppelin typically carried 3,500 kg (7,700 lb) of ballast water and 650 kg (1,430 lb) of spare parts, including an extra propeller. Calcium chloride was added to the ballast water to prevent freezing. The ship retained grey water from the sinks for use as additional ballast. Both fresh and waste water could be moved forward and aft to control trim.

Graf Zeppelin dropping water ballast during landing

Graf Zeppelin dropping water ballast during landing

The airship usually took off vertically using static lift (buoyancy), then started the engines in the air, adding aerodynamic lift. Normal cruising altitude was 200 m (650 ft); it climbed if necessary to cross high ground or poor weather, and often descended in stormy weather. To measure the wind speed over the sea, and calculate drift, floating pyrotechnic flares were dropped.

When preparing to land the crew advised the ground, either by radio or signal flag. Ground crew lit a smoky fire, to help the airshipmen judge wind speed and direction. The airship slowed, then adjusted buoyancy to neutral by valving off hydrogen or dropping ballast. Echo sounding with the report from an 11-mm blank round was used to measure altitude accurately. The ship flew in with its nose trimmed slightly down, made its final approach into the wind descending at 30 m (100 ft) per minute, then used reverse thrust to stop over the landing flag, where it dropped ropes to the ground. Landing in rough weather required a faster approach. Up to 300 people manhandled the airship into a hangar or secured it by the nose to a mooring mast.

Graf Zeppelin's top airspeed was 128 km/h (36 m/s; 80 mph; 69 kn) at 1,980 kW (2,650 hp); it cruised at 117 km/h (33 m/s; 73 mph; 63 kn), at 1,600 kW (2,150 hp). It had a total lift capacity of 87,000 kg (192,000 lb) with a usable payload of 15,000 kg (33,000 lb) on a 10,000 km (6,200 mi; 5,400 nmi) flight. It was slightly unstable in yaw, and to make it easier to fly, had an automatic pilot which stabilised it in that axis. Pitch was controlled manually by an elevatorman who tried to limit the angle to 5° up or down, so as not to upset the bottles of wine which accompanied the elaborate food served on board. Operating the elevators was so demanding and strenuous that an elevatorman's shift was only four hours, reduced to two in rough weather.

The design and construction of Graf Zeppelin were essentially conservative, based on tried-and-true technology developed over the Zeppelin Company’s decades of experience, and the ship was constructed of triangular Duralumin girders, with frames (or “rings”) spaced 15 meters apart.

The shape and size of Graf Zeppelin was not ideal aerodynamically (in terms of performance), structurally (in terms of strength), or economically (in terms of payload).

The design of the ship was determined — and limited — by the size of the construction shed at Friedrichshafen, which had inner dimensions of 787 feet in length and 115 feet in height.

Since greater size meant greater efficiency in long distance operation, the challenge for Ludwig Dürr and his design team was to create a ship with the largest possible gas capacity that could be built within the confines of the construction shed.

The Graf Zeppelin’s hull was the largest shape that could be built within the rectangular limits of the Friedrichshafen construction shed. The ship was designed to have the maximum gas-carrying capacity that could be built with the limits of the shed.

The ship they designed was a long, thin cylinder, 776 feet long and 100 feet in diameter, with a gondola situated far forward, so that it could be slung under the hull where it began to rise toward the bow. The height of the ship from the bottom of the gondola to the top of the hull was 110 feet, just barely clearing the arches of the shed.

LZ-127’s long, slim hull was not the most aerodynamically efficient shape (which was a lesson learned from the efficient teardrop design of Bodensee and Nordstern); it was not the most structurally effective shape (since the thin hull was vulnerable to bending stresses); and it was not the most economically practical design (since its relatively small size limited payload on long flights), but it was the best that could be achieved within the limitations of the hangar at Friedrichshafen.

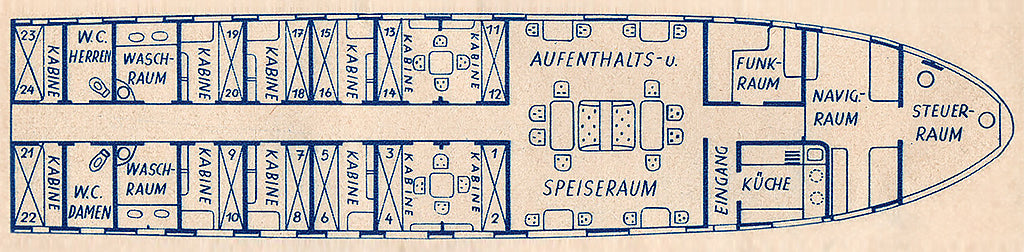

Deckplan of Graf Zeppelin’s Gondola

Deckplan of Graf Zeppelin’s Gondola

Behind the front command cabin through a door lay the map room, with two large open access hatches to allow the command crew to communicate with the navigators. From the map room ascending a ladder allowed access to a keel corridor inside the hull. The map room had two large windows, one on each side. A rear door led from the map room to a central corridor with the three-man radio room to the left and the electric kitchen to the right, and a short passage to the main entrance-exit door on the right.

The corridor ended at a door that opened into the main dining and sitting room, with four large windows. At the rear of this room a door opened into the long corridor to access the passenger's cabins and washrooms and toilet facilities. Each passenger cabin was designed in the "Pullman" style as enjoyed on luxury train travel. By day was set with a sofa which by night the crew would convert to two beds, one above the other. The crew's quarters were inside the hull reached by a catwalk. The kitchen was equipped with a single electric oven with two compartments and hot plates on top.

The main generating plant was in a separate compartment mostly inside the hull. Two 8.9 kW (12 hp) Wanderer car engines adapted to burn Blau gas, only one of which operated at a time, drove two Siemens & Halske dynamos each. One dynamo on each engine powered the oven and hotplates, and one the lighting and gyrocompass. Cooling water from these engines heated radiators inside the passenger lounge. Two ram air turbines attached to the main gondola on swinging arms provided electrical power for the radio room, internal lighting, and the galley. Batteries could power essential services like radios for half an hour, and there were small petrol generators for emergency power.

Three radio operators used a one-kilowatt vacuum tube transmitter (about 140 W antenna power) to send telegrams over the low frequency (500–3,000 m) bands. A 70 W antenna power emergency transmitter carried telegraph and radio telephone signals over 300–1,300 m wavelength bands. The main aerial consisted of two lead-weighted 120-metre (390 ft)-long wires deployed by electric motor or hand crank; the emergency aerial was a 40-metre (130 ft) wire stretched from a ring on the hull. Three six-tube receivers served the wavelengths from 120 to 1,200 m (medium frequency), 400 to 4,000 m (low frequency) and 3,000 to 25,000 m (overlapping low frequency and very low frequency). The radio room also had a shortwave receiver for 10 to 280 m (high frequency).

A radio direction finder used a loop antenna to determine the airship's bearing from any two land radio stations or ships with known positions. During the first transatlantic flight in 1928, the radio room sent 484 private telegrams and 160 press telegrams.

The ship typically cruised at 72 MPH, at an altitude of 650 feet above ground level, but it also flew as high as 6,000 feet on occasion (for example, when crossing the Stanovoy mountain range in far eastern Russia during its Round-the-World flight). Graf Zeppelin also cruised well below 650 feet when necessary, as it was German practice to reduce the stress of vertical gusts by flying low to the ground during storms when possible.

The Use of Blau Gas

But Graf Zeppelin did incorporate one especially notable innovation, in the use of Blau gas fuel for its five engines. One of the challenges of lighter-than-air powered flight has always been the need to account for the loss of weight as fuel is burned by the ship’s engines. As gasoline or diesel fuel is consumed during flight, the ship becomes lighter, and without a means to compensate for this change, lifting gas must be vented to maintain the ship’s equilibrium. The Zeppelin Company’s innovative solution to this issue with Graf Zeppelin was the use of a gaseous fuel, similar to propane, named Blau gas after its inventor, Dr Hermann Blau. Since Blau gas is similar in weight to air, its consumption during flight did not significantly change the aerostatic balance of the ship, and so it was not necessary to valve lifting gas to compensate for Blau gas burned by the engines.

Blau gas was also more efficient to carry than gasoline, and extended the ship’s range by over 30 hours of flying time; the approximately one million cubic feet of Blau gas carried by Graf Zeppelin could power the ship for over one hundred hours, but if that million cubic feet of Blau gas had been replaced by hydrogen, the additional hydrogen could have lifted only enough gasoline to power the ship for 70 hours or less.

The Blau gas was carried in 12 cells (Kraftgaszelle, or “power gas cells”), in the lower section of 12 of the ship’s 17 gas cell bays, beneath the hydrogen cells (Traggaszelle, or “lift gas cells”). Of Graf Zeppelin’s total gas capacity of 3,707,550 cubic feet, 1,059.300 cubic feet was available for Blau gas. The ship did also carry a supply of gasoline, so that if the ship were heavy, the engines could burn gasoline instead of Blau gas, lightening the ship without the need to drop ballast.

The use of Blau gas was quite hazardous, and many people believe Graf Zeppelin’s Blau gas presented a greater danger to safety than the ship’s hydrogen. The gas cells of that era were not impermeable and always leaked to some extent, and small tears and other minor leaks were also common. Since Blau gas has a similar density to air, escaping Blau gas did not rise like hydrogen but rather settled to the bottom of the hull, including the keel and into the gondola itself, and could even flow out toward the engines. This was an even bigger problem when the ship was on the ground, especially inside an enclosed hangar, since there was no flow of air to carry the gas away.

It should always be remembered that Graf Zeppelin was basically an experimental “proof of concept” design, and that the design of ship was limited by practical considerations such as the size of the construction shed at Friedrichshafen. While a clever response to these limitations in some ways, Blau gas had never before been used in a zeppelin, and it would never be used again.

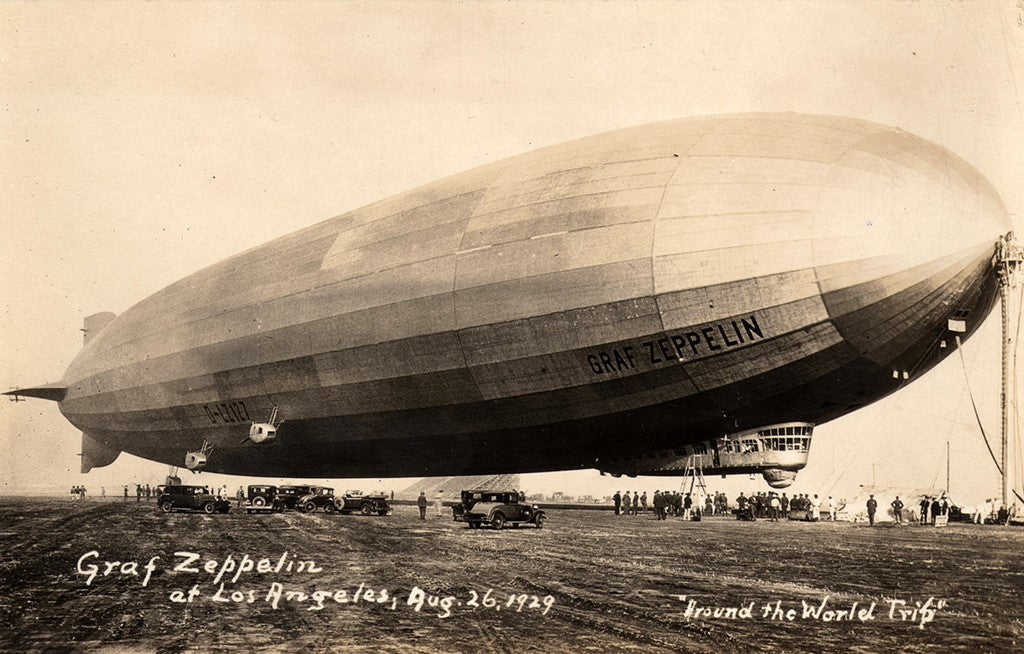

Graf Zeppelin landing at Los Angeles, 1929

Graf Zeppelin landing at Los Angeles, 1929

- Operational history -

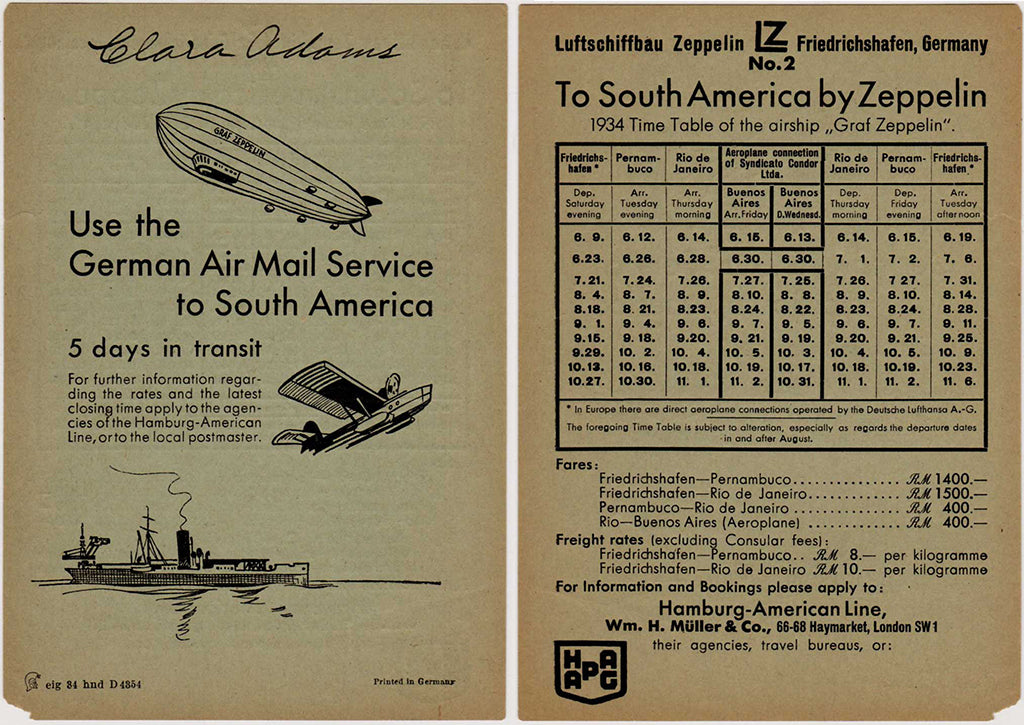

The LZ 127 was christened Graf Zeppelin by Countess Brandenstein-Zeppelin on 8 July 1928, after her father Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the founder of the company, on the 90th anniversary of his birth. During most of its career, it was operated by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin's commercial flight arm, DELAG, in conjunction with the Hamburg-American Line (HAPAG); for its final two years it flew for the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei (DZR).

Passengers paid premium fares to fly on the Graf Zeppelin (1,500 ℛℳ from Germany to Rio de Janeiro in 1934, equal to $590 then, or $12,000 in 2018 dollars), and fees collected for valuable freight and air mail also provided income. On the first transatlantic flight, Graf Zeppelin carried 66,000 postcards and covers.

Dr. Hugo Eckener had earned his doctorate in Psychology at Leipzig University under Wilhelm Wundt, and could use his knowledge of mass psychology to the benefit of the Graf Zeppelin. He identified safety as the most important factor in the ship's public acceptance, and was ruthless in pursuit of this. He took complete responsibility for the ship, from technical matters, to finance, to arranging where it would fly next on its years-long public relations campaign, in which he promoted "zeppelin fever". On one of the Brazil trips British Pathé News filmed on board. Dr. Hugo Eckener cultivated the press, and was gratified when the British journalist Lady Grace Drummond-Hay wrote, and millions read, that:

The Graf Zeppelin is a ship with a soul. You have only to fly in it to know that it's a living, vibrant, sensitive and magnificent thing.

Graf Zeppelin was greeted by large crowds on most of its early voyages. There were 100,000 at Moscow and possibly 250,000 at Tokyo to see it. At Stockholm, spectators launched firework rockets around it, and on the return flight from Moscow it was punctured by rifle shots near the Soviet Union-Lithuania border. On one visit to Rio de Janeiro people released hundreds of small toy petrol-burning hot air balloons near the flammable craft. The airship captured the public imagination and was used extensively in advertising. On visits to England, it photographed Royal Air Force bases, the Blackburn aircraft factory in Yorkshire, and the Portsmouth naval dockyard; it is likely that this was espionage at the behest of the German government.

Proving flights (1928)

During 1928, there were six proving flights. On the fourth one, Blau gas was used for the first time. Graf Zeppelin carried Oskar von Miller, head of the Deutsches Museum; Charles E. Rosendahl, commander of USS Los Angeles; and the British airshipmen Ralph Sleigh Booth and George Herbert Scott. It flew from Friedrichshafen to Ulm, via Cologne and across the Netherlands to Lowestoft in England, then home via Bremen, Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden, a total of 3,140 kilometres (1,950 mi; 1,700 nmi) in 34 hours and 30 minutes. On the fifth flight, Dr. Hugo Eckener caused a minor controversy by flying close to Huis Doorn in the Netherlands, which some interpreted as a gesture of support for the former Kaiser Wilhelm II who was living in exile there.

First intercontinental flight (1928)

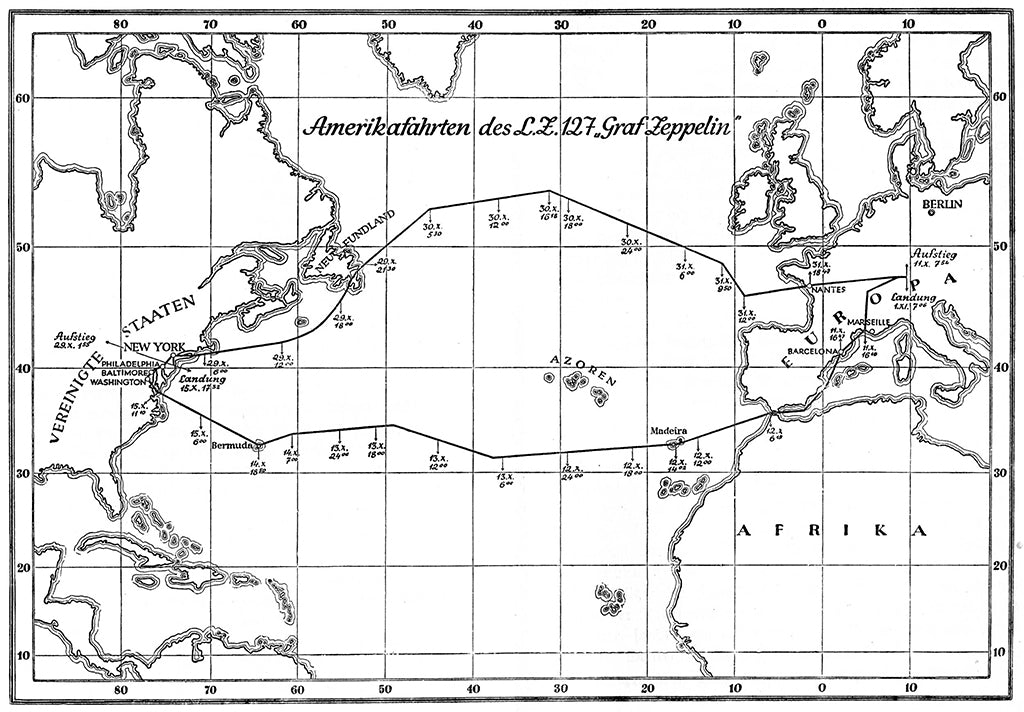

Graf Zeppelin’s route across the Atlantic

Graf Zeppelin’s route across the Atlantic

Dr. Hugo Eckener commanded the "Graf Zeppelin" on its first intercontinental trip, a transatlantic crossing which left Friedrichshafen, Germany, at 07:54 on 11 October 1928, and arrived in the United States at NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey, on 15 October after having travelled 9,926 km in 111 hours. Notwithstanding the heavy headwinds and stormy weather that slowed the journey, Dr. Hugo Eckener had nevertheless repeated the success of his first transatlantic crossing made four years earlier in October 1924, to deliver the D-LZ126 (renamed the USS Los Angeles) to the U.S. Navy. Dr. Hugo Eckener and the crew were welcomed enthusiastically with a "ticker tape" parade in New York the next day and a subsequent invitation to the White House.

This first transatlantic trip was not without its difficulties, however, as the airship suffered potentially serious damage to its port tail fin on the third day of the flight when a large section of the linen covering was ripped loose while passing through a mid-ocean weather front or squall line. With the engines stopped, the ship's riggers attended to repairs the torn fabric to the framework and sew blankets to the ship's envelope. Fortunately the riggers finished just before Dr. Hugo Eckener had to restart the engines when the ship had dropped to two hundred feet of the ocean's surface. The Graf crossed the U.S. coast at Cape Charles, Virginia, around 10 AM on 15 October, passed over Washington, D.C., at 12:20PM, Baltimore, MD, at 1PM, Philadelphia, PA, at 2:40 PM, New York City at 4 PM, and landed at NAS Lakehurst at 5:38 PM.

The damaged port fin after arrival at Lakehurst

The damaged port fin after arrival at Lakehurst

In addition to the passengers and crew, there was also a stowaway on the fight, 19-year old Clarence Tehune, who had secreted himself onboard the Graf Zeppelin at Friedrichshafen and working for his passage in the airship's kitchen. Terhune was returned to Europe on the French liner SS Ile de France along with a number of airship crewmembers.

Mediterranean flights (1929)

Graf Zeppelin visited Palestine in late March 1929. At Rome it sent greetings to Benito Mussolini and King Victor Emmanuel III. It entered Palestine, flew over Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and descended to near the surface of the Dead Sea, 430 m (1,400 ft) below sea level. The ship delivered 16,000 letters in mail drops at Jaffa, Athens, Budapest and Vienna. The Egyptian government (under pressure from Britain) refused it permission to enter their airspace. The second Mediterranean cruise flew over France, Spain, Portugal and Tangier, then returned home via Cannes and Lyon on 23–25 April.

The "Interrupted Flight" (1929)

While the "Graf Zeppelin" would eventually have a safe and highly successful nine-year career, the airship was almost lost just a half a year after its maiden flight while attempting to make its second trip to the United States in May 1929. Shortly after dark on 16 May, the first night of the flight , the airship lost two of its five engines while over the Mediterranean off the southwest coast of Spain forcing Dr. Hugo Eckener to abandon the trip and return to Friedrichshafen. While flying up the Rhône Valley in France against a stiff headwind the next afternoon, however, two of the remaining three engines also failed and the airship began to be pushed backwards toward the sea.

As Dr. Hugo Eckener desperately looked for a suitable place to put down the airship, the French Air Ministry advised him that he would be permitted to land at the Naval Airship Base at Cuers-Pierrefeu about ten miles from Toulon to use the mooring mast and hangar of the lost airship Dixmude (France's only dirigible which crashed the Mediterranean in 1923) if the Graf could reach the facility before being forced out to sea. Although barely able to control the Graf on its one remaining engine, Dr. Hugo Eckener managed to make a difficult but successful emergency night landing at Cuers. After making temporary repairs, the Graf finally returned to Friedrichshafen on May 24. Mail carried on the flight received a one-line cachet reading "Due to mishap the flight was delayed for the first America trip" and was held at Friedrichshafen until 1 August 1929, when the airship made another attempt to cross the Atlantic for Lakehurst arriving on 4 August 1929. Four days later, the "Graf Zeppelin" departed Lakehurst for another daring enterprise - a complete circumnavigation of the globe.

Round-the-world flight (1929)

Map of Round-the-World flight

Map of Round-the-World flight

The American newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst's media empire paid half the cost of the project to fly Graf Zeppelin around the world, with four staff on the flight; Lady Hay Drummond-Hay, Karl von Wiegand, the Australian explorer Hubert Wilkins, and the cameraman Robert Hartmann. Drummond-Hay became the first woman to circumnavigate the world by air. Hearst stipulated that the flight in August 1929 officially start and finish at Lakehurst. Round-the-world tickets were sold for almost $3000 (equivalent to $47,000 in 2021), but most participants had their costs paid for them.The flight's expenses were offset by the carriage of souvenir mail between Lakehurst, Friedrichshafen, Tokyo, and Los Angeles. A US franked letter flown on the whole trip from Lakehurst to Lakehurst required $3.55 (equivalent to $56 in 2021) in postage.

Graf Zeppelin set off from Lakehurst on 8 August, heading eastwards. The ship refuelled at Friedrichshafen, then continued across Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Tokyo. After five days at a former German airship shed that had been removed from Jüterbog and rebuilt at Kasumigaura Naval Air Station, Graf Zeppelin continued across the Pacific to California. Dr. Hugo Dr. Hugo Eckener delayed crossing the coast at San Francisco's Golden Gate so as to come in near sunset for aesthetic effect. The ship landed at Mines Field in Los Angeles, completing the first ever nonstop flight across the Pacific Ocean. The takeoff from Los Angeles was difficult because of high temperatures and an inversion layer. To lighten the ship, six crew were sent on to Lakehurst by aeroplane. The airship suffered minor damage from a tail strike and barely cleared electricity cables at the edge of the field. The Graf Zeppelin arrived back at Lakehurst from the west on the morning of 29 August, three weeks after it had departed to the east.

Flying time for the four Lakehurst to Lakehurst legs was 12 days, 12 hours, and 13 minutes; the entire circumnavigation (including stops) took 21 days, 5 hours, and 31 minutes to cover 33,234 km (20,651 mi; 17,945 nmi). It was the fastest circumnavigation of the globe at the time.

Dr. Hugo Eckener became the tenth recipient and the third aviator to be awarded the Gold Medal of the National Geographic Society, which he received on 27 March 1930 at the Washington Auditorium. Before returning to Germany, Dr. Hugo Eckener met President Herbert Hoover, and successfully lobbied the US Postmaster General for a special three-stamp issue (C-13, 14 & 15) for mail to be carried on the Europe-Pan American flight due to leave Germany in mid-May. Germany issued a commemorative coin celebrating the circumnavigation.

Europe-Pan American flight (1930)

Graf Zeppelin fly over Wembley Stadium

Graf Zeppelin fly over Wembley Stadium

On 26 April 1930, Graf Zeppelin flew low over the FA Cup Final at Wembley Stadium in England, dipping in salute to King George V, then briefly moored alongside the larger R100 at Cardington. On 18 May, it left on a triangular flight between Spain, Brazil, and the US, carrying 38 passengers, many of them in crew accommodation. The ship arrived at Recife (Pernambuco) in Brazil, docking at Campo do Jiquiá on 22 May, where 300 soldiers helped land it. It then flew to Rio de Janeiro, where there was no post to tether to, so it was held down by the landing party for the two hours of the visit.

It flew north, via Recife, to Lakehurst; a storm damaged the rear engine nacelle, which had to be repaired in the hangar at Lakehurst. During ground handling of the airship there, it suddenly lifted, causing serious injury to one of the US Marines who was assisting. A few hours from home, when the Graf Zeppelin flew through a heavy hailstorm over the Saône, the envelope was damaged and the ship lost lift. Dr. Hugo Eckener ordered full power and flew the ship out of trouble, but it came within 200 feet of hitting the ground.

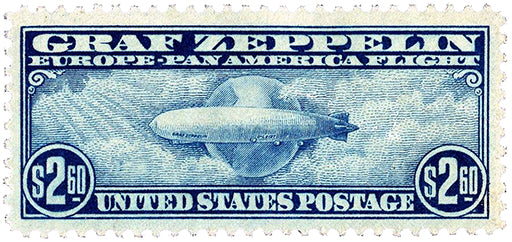

The Europe-Pan American flight was largely funded by the sale of special stamps issued by Spain, Brazil, and the US for franking mail carried on the trip. The US issued stamps in three denominations: 65¢, $1.30, and $2.60, all on 19 April 1930.

$2.60 Europe-Pan American stamp

$2.60 Europe-Pan American stamp

Middle East flight (1931)

The "Graf Zeppelin" made two visits to the Middle East during its career. The first took place over four days in April 1929, without landing but during which mail was dropped to the large German colony at Jaffa in Palestine. The second flight took place in 1931 beginning on 9 April with a flight to Cairo, Egypt, where the airship landed less than two days later. After a brief stop the "Graf Zeppelin" proceeded on to Palestine before returning to Friedrichshafen on 23 April, just an hour over four days after departure. The trip took 97 hours, covered 9,000 kilometres and crossed 14 countries on three continents.

Polar flight (1931)

Graf Zeppelin landing on water during polar flight

Graf Zeppelin landing on water during polar flight

The ship pursued another spectacular destination in July 1931 with a research trip to the Arctic; this had already been a dream of Count Zeppelin 20 years earlier, which could not, however, be realized at the time due to the outbreak of war.

In July 1930, Dr. Hugo Eckener had already piloted the Graf on a three-day trip to Norway and Spitsbergen, in order to determine its performance in this region. Shortly after Dr. Hugo Eckener made a three day flight to Iceland, both trips completed without technical problems.

The initial idea was to rendezvous with the submarine Nautilus, the ship of polar researcher George Hubert Wilkins, who was attempting a trip under the ice. This plan was abandoned when the submarine encountered recurring technical problems, leading to its eventual scuttling in a Bergen fjord.

Dr. Hugo Eckener instead began to plan a rendezvous with a surface vessel. He intended funding to be secured by delivering mail post to the ship. After advertising, around fifty thousand letters were collected from around the world weighing a total of about 300 kilograms. The rendezvous vessel, the Russian icebreaker Malygin, on which the Italian airshipman and polar explorer Umberto Nobile was a guest, required another 120 kilograms of post. The major costs of the expedition were met solely by sale of postage stamps. The rest of the funding came from Aeroarctic and the Ullstein-Verlag in exchange for exclusive reporting rights.

The 1931 polar flight took one week from 24 June 1931 until the 31st. The Graf travelled about 10,600 kilometres, the longest leg without refuelling was 8,600 kilometres. The average speed was 88 km/h.

South American operations (1931–1937)

Graf Zeppelin’s service to South America

Graf Zeppelin’s service to South America

From the beginning, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin had plans to serve South America. There was a large community of Germans in Brazil, and existing sea connections were slow and uncomfortable. Graf Zeppelin could transport passengers over long distances in the same luxury as an ocean liner, and almost as quickly as contemporary airliners.

Graf Zeppelin made three trips to Brazil in 1931 and nine in 1932. The route to Brazil meant flying down the Rhône valley in France, a cause of great sensitivity between the wars. The French government, concerned about espionage, restricted it to a 12 nmi (22 km; 14 mi)-wide corridor in 1934. Graf Zeppelin was too small and slow for the stormy North Atlantic route, but because of the Blau gas fuel, could carry out the longer South Atlantic service. On 2 July 1932 it flew a 24-hour tour of Britain.

While returning from Brazil in October 1933, Graf Zeppelin stopped at NAS Opa Locka in Miami, Florida, and then Akron, Ohio, where it moored at the Goodyear Zeppelin airdock. The airship then appeared at the Century of Progress World's Fair in Chicago. It displayed swastika markings on the left side of the fins, as the Nazi Party had taken power in January. Dr. Hugo Dr. Hugo Eckener circled the fair clockwise so that the swastikas would not be seen by the spectators. The United States Post Office Department issued a special 50-cent airmail stamp (C-18) for the visit, which was the fifth and final one the ship made to the US.

The airship's cotton envelope absorbed moisture from the air in humid tropical conditions. When the relative humidity reached 90%, the ship's weight rose by almost 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lb). Exposure to tropical downpours could greatly add to this, but when under way the ship had enough reserve power to generate dynamic lift to compensate. In April 1935 it made a rough forced landing at Recife after it was caught in a rainstorm at low speed on the approach to land and the added weight of several tons of water caused it to sink to the ground. The lower rudder was lost, the outer envelope was ripped in several places, and a petrol tank was punctured by a palm tree.

Graf Zeppelin flying near the Barolo Palace in Buenos Aires

Graf Zeppelin flying near the Barolo Palace in Buenos Aires

In late 1935 Graf Zeppelin operated a temporary postal shuttle service between Recife and Bathurst, in the British African colony of the Gambia. On 24 November, during the second trip, the crew learned of an insurrection in Brazil, and there was some doubt whether it would be possible to return to Recife. Graf Zeppelin delivered its mail to Maceió, then loitered off the coast for three days until it was safe to land, after a flight of 118 hours and 40 minutes.

Brazil built a hangar for airships at Bartolomeu de Gusmão Airport, near Rio de Janeiro, at a cost of $1 million (equivalent to $20 million in 2018). Brazil charged the DZR $2000 ($39,000) per landing, and had agreed that German airships would land there 20 times per year, to pay off the cost. The hangar was constructed in Germany and the parts were transported and assembled on site. It was finished in late 1936, and was used four times by Graf Zeppelin and five by Hindenburg. It now houses units of the Brazilian Air Force.

Airship hangar near Rio de Janeiro

Airship hangar near Rio de Janeiro

Propaganda (1936)

Dr. Hugo Eckener was outspoken about his dislike of the Nazi Party, and was warned about it by Rudolf Diels, the head of the Gestapo. When the Nazis gained power in 1933, Joseph Goebbels (Reich Minister of Propaganda) and Hermann Göring (Commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe) sidelined Dr. Hugo Eckener by putting the more sympathetic Lehmann in charge of a new airline, Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei (DZR), which operated German airships.

On 7 March 1936, in violation of the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties, German troops reoccupied the Rhineland. Hitler called a plebiscite for 29 March to retrospectively approve the reoccupation, and adopt a list of exclusively Nazi candidates to sit in the new Reichstag. Goebbels commandeered Graf Zeppelin and the newly launched Hindenburg for the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The airships flew in tandem around Germany before the vote, with a joint departure from Löwenthal on the morning of 26 March. They toured the country for four days and three nights, dropping propaganda leaflets, playing martial music and slogans from large loudspeakers, and broadcasting political speeches from a makeshift radio studio on Hindenburg.

Golden age

Graf Zeppelin flying above an ocean liner

Graf Zeppelin flying above an ocean liner

The Graf Zeppelin undertook a number of trips around Europe, landing at both Cardington and also at Hanworth aerodrome (a future Heathrow Airport)

Following a successful tour to South America in May 1930, it was decided to open the first regular transatlantic airship line, travelling mainly from Germany to Brazil (64 such round trips overall) with occasional stops, among them Spain, Miami, London, and Berlin. At one of the Berlin visits a glider that was released from under its hull performed a loop in front of cheering crowds, and on one of the Brazil trips British Pathé News filmed on board.

Almost every flight had a reporter on board, who would radio a report to the ground via Morse Code. Such articles made Lady Drummond-Hay famous, and she would be pictured in advertisements featuring the Graf.

In October 1933, the Graf Zeppelin made an appearance at the Century of Progress World's Fair in Chicago, after circling over the fair, then landing and relaunching 25 minutes later. Despite the beginning of the Great Depression and growing competition by fixed-wing aircraft, D-LZ127 would transport an increasing number of passengers and mail across the ocean every year until 1937.

Post and cargo provided most of the income for operating the Graf. In one transatlantic flight the Graf would carry 52,000 postcards and 50,000 letters, and by its last flight it had carried 53 tonnes of mail. Since 1912, Zeppelins were allowed to postmark and sort mail onboard and the Graf managed to deliver South America-bound about a week faster than by ship. When the Hindenburg entered service in 1936 prospects became better and a profit was expected for 1937 by delivering mail on both it and the Graf, but the Hindenburg's loss in May 1937 put an end to all commercial Zeppelin service.

End of an era

The crew heard of the Hindenburg disaster by radio on 6 May 1937 while in the air, returning from Brazil to Germany; they delayed telling the passengers until after landing on 8 May so as not to alarm them. The disaster, in which Lehmann and 35 others were killed, destroyed public faith in the safety of hydrogen-filled airships, making continued passenger operations impossible unless they could convert to non-flammable helium. Hindenburg had originally been planned to use helium, but almost all of the world's supply was controlled by the US, and its export had been tightly restricted by the Helium Act of 1925.

Graf Zeppelin was permanently withdrawn from service shortly after the disaster. On 18 June, its 590th and last flight took it to Frankfurt am Main, where it was deflated and exhibited to visitors in its hangar. President Roosevelt supported exporting enough helium for the Hindenburg-class LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II to resume commercial transatlantic passenger service by 1939, but by early 1938, the opposition of Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, who was concerned that Germany was likely to use the airship in war, made that impossible. On 11 May 1938, Roosevelt's press secretary announced that the US would not sell helium to Germany. Dr. Hugo Eckener, who had unsuccessfully intervened, responded that it would be "the death sentence for commercial lighter-than-air craft." Graf Zeppelin II made 30 test, promotional, propaganda and military surveillance flights around Europe using hydrogen between September 1938 and August 1939; it never entered commercial passenger service. On 4 March 1940, Hermann Göring ordered Graf Zeppelin and Graf Zeppelin II to be scrapped, and their airframes to be melted down for the German military aircraft industry.

During its career, Graf Zeppelin had flown almost 1.7 million km (1,053,391 miles), the first aircraft to fly over a million miles. It made 144 oceanic crossings (143 across the Atlantic, and one of the Pacific), carried 13,110 passengers and 106,700 kg (235,300 lb) of mail and freight. It flew for 17,177 hours (717 days, or nearly two years), without injuring a passenger or crewman. It has been called "the world's most successful airship", but it was not a commercial success; it had been hoped that the Hindenburg-class airships that followed would have the capacity and speed to make money on the popular North Atlantic route. Graf Zeppelin's achievements showed that this was technically possible.

By the time the two Graf Zeppelins were recycled, they were the last rigid airships in the world, and heavier-than-air long-distance passenger transport, using aircraft like the Focke-Wulf Condor and the Boeing 307 Stratoliner, was already in its ascendancy.Aeroplanes were faster, less labour-intensive and safer; by 1958 they developed into passenger jets like the Boeing 707 which could cross the Atlantic reliably in a few hours. By 2017 annual air passenger journeys had surpassed 4 billion.

Modern airships like the Zeppelin NT use semi-rigid designs, and are lifted by helium on their mainly sight-seeing duties.

Graf Zeppelin profile, showing rings, gas cells, and major elements.

Graf Zeppelin profile, showing rings, gas cells, and major elements.

General characteristics

Role: Commercial passenger airship

National origin: Germany

Manufacturer: Luftschiffbau Zeppelin

Designer: Ludwig Dürr

First flight: 18 September 1928

Introduction: 11 October 1928

Retired: 18 June 1937

Status: Scrapped March 1940

Career

Construction number: LZ 127

Registration: D-LZ 127

Radio code: DENNE

Owners and operators: Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft; from 1935, Deutsche Zeppelin

Reederei

Flights: 590

Total hours: 17,177

Total distance: 1.7 million km (1.06 million miles)

Crew: 36

Capacity: 20 passengers / Typical disposable load 19,900 kg (43,900 lb)

Length: 236.6 m (776 ft 3 in)

Diameter: 30.5 m (100 ft 1 in) maximum

Fineness ratio: 7.25

Height: 33.5 m (109 ft 11 in)

Volume: 75,000 m3 (2,600,000 cu ft) hydrogen + 30,000 m3 (1,100,000 cu ft) Blau gas capacity

Number of gas cells: 16

Empty weight: 67,100 kg (147,930 lb)

Fuel capacity: 8,000 kg (18,000 lb) petrol + 30,000 m3 (1,100,000 cu ft) Blau gas

Useful lift: 87,000 kg (192,000 lb) typical gross lift

Powerplant: 5 × Maybach VL II V-12 water-cooled reversible piston engines, 410 kW (550 hp) each

Propellers: 2, later 4-bladed propellers

Performance

Maximum speed: 128.16 km/h (79.63 mph, 69.20 kn)Range: 10,000 km (6,200 mi, 5,400 nmi) at 117 km/h (73 mph; 63 kn)

1/1000 German Graf Zeppelin Airship D-LZ127 Precision Structure Model Kit

1/1000 German Graf Zeppelin Airship D-LZ127 Precision Structure Model Kit

- General sources -

Airships.net LZ-127 Graf ZeppelinWikipedia.org LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin